Finding: Site-Sourced Design

in Perspectives

by Nina Ebbighausen, AIA, LEED AP

“[Our job is] not to reproduce the visible, but to make visible.”

–Paul Klee

“The sun never knew how great it was until it hit the side of a building.”

–Louis Kahn

Introduction

In our fast-paced and nebulous digital world, architecture that has an integral relationship to its site can help to emphasize the present moment and ground us in our bodies. To do this most effectively, these architectural installations must engage our bodies in multi-sensory ways that heighten our experience of the site while also increasing our awareness of ourselves in relation to that site. In order to bring us into the “here and now,” it’s important that these installations tap into qualities and conditions of the existing site rather than creating a proxy environment that can actually disconnect our bodies from the real place and real time.

To do this—to design engaging and authentically site-based installations—it’s desirable to spend time in a place, looking, listening, smelling, touching, even tasting, until meaningful connections begin to form between the observer and the site. Not all sites are initially memorable, and connections often must be forged between the occupant and subtle or fleeting conditions—like the brief glow of sunlight off a rocky cliff at sundown; the shared filigree quality of tree branches and power line structures; or the near/far connections generated when we rest our bodies in one place while we listen to distant worlds through the soundscape. Indeed, even beautiful landscapes become more personal and meaningful for us when we move beyond just the pretty view in general and focus on creating more precise ways to enhance our awareness of, and connect our bodies with, that place.

In his article, “Site, Ascendant,” David Heymann explores the potential of site as source, rather than just setting, for works of art in the last 50 years. Andy Goldsworthy’s installation, “Rain Shadow” is an example of site as source—“the transitory nature of the work is a form of appreciation of a particular place at a particular moment.” 1 Artworks which “identify or expose or respect or strengthen the explicit value of each location—each site—as it structures… experience” can be set in natural landscapes as well as in urban conditions.2

Consider, for example, how James Turrell’s 2005 Sky Pesher installation in Minneapolis curates its architectural setting to enhance our awareness of the changing qualities of light and the sky (during the course of the day, over the changing seasons…). Sky Pesher is much more effective at producing explicit awareness of these conditions than is a conventional picture window. It does this by giving us a comfortable place to rest our bodies, removing competing views, and creating a neutral architectural background that helps to focus our gaze to the open-air skylight above. Further, by minimizing the thickness of the skylight frame, Turrell dematerializes the room’s ceiling, letting the sunlight and sky appear dominant and almost tangible.

Also consider how the underground placement of Sky Pesher—arrived at through a choreographed procession that leads from a downtown Minneapolis museum, to a hillside (which we must climb), through a darkened and elongated entrance portal, and finally into an underground viewing chamber—encourages us to contemplate the sky specifically in relation to the surrounding earth, and in opposition to its urban context.

So, how specifically does one proceed with site as a primary form-driver for architectural design? Christophe Girot offers a model in his article, “Four Trace Concepts in Landscape Architecture.” Girot acknowledges that designers seldom belong to the place in which they are asked to intervene, and he offers four stages of landscape investigation—Landing, Grounding, Finding, and Founding—to enable the site to emerge in a comprehensible manner. 3 Girot roots his process in an embodied exploration—one in which the designer engages their own senses and memory—and he notes that “the recovery of landscape will begin only when we are ready to reconcile our sense with our science.” 4

Girot’s third concept, Finding, is most informative for catalyzing design work that grows authentically out of the site, finding its raison d’être within the place itself, and enhancing the visitor’s engaged understanding or perceptions of that place. During Finding, a design proposition grows out of a deep and intimate understanding of existing conditions; it is not imposed. In turn, these existing conditions provide deeper historical and cultural context for the design work than any we can fabricate from our imaginations alone. This is an open-ended process with open-ended possibilities because of the importance of chance and indeterminacy in discovery.

“Architecture is the art of reconciliation between ourselves and the world, and this mediation takes place through the senses.”

– Juhani Pallasmaa. The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses. 5

Explorations

The potential of site as design source and Girot’s processes were tested over the course of ten architectural studios at the University of Minnesota School of Architecture, starting in 2010, which focused on site as a catalyst for form-making. Students were asked to each design a site-specific “installation” that engages visitors in specific ways in order to reveal an aspect of the site that would otherwise be easily overlooked by these visitors. Revealing something subtle, hidden, or latent about the site—something not otherwise immediately evident or fully appreciated—could involve strategies such as intensification, transformation, extension, subversion, and comparison. Students were asked to engage actual site conditions in their design proposals as opposed to providing a “surrogate,” or stand-alone experience, according to the following two criteria:

- If you could transplant your proposal to another site and have it work essentially just as well, your proposal is NOT adequately site-specific. You will need to understand your site intimately to determine which aspects you will need to respond to and reveal to make this a site-specific installation. An installation which is completed by the site itself is generally considered site specific.

- Similarly, avoid the temptation to create a “Disney World” proxy version of your site within your installation. It is a requirement of this assignment that the real site itself—not a facsimile of the site—is engaged by your design and is necessary to complete your installation.

It was expected that students would need to engage at “arm’s length” and in sensory ways in order to complete the assignment. They were encouraged to make in-site constructions to experimentally mediate and push the envelope of how their own bodies apprehended the site and to see whether some latent site condition became more evident because of their experimental intervention. As part of their design work, they were required to compose a precise journey by which a visitor would discover and experience the installation—in other words, experience needed to be curated in relation to surrounding conditions and to unfold over time. Further, the installation was not intended to be simply observed from afar; the installation was considered incomplete without the active inhabitation or participation in some particular way of visitors / inhabitants with and around the form.

Examples

Following are examples of student design work stemming from the processes noted, reflecting site as source, and engaging occupants in a fundamentally embodied and sensory understanding of place.

Student Anna Dresang, in the University of Minnesota BS Arch degree program, proposed a project entitled “Heightened Thrill” in 2021, in which she indicated: “By [harnessing] the contrasting sensations of floating and being buried, this installation heightens the sense of peril and thrill that already exists within the precarious ruins and [Minneapolis Mill Ruins Park] site as a whole.”

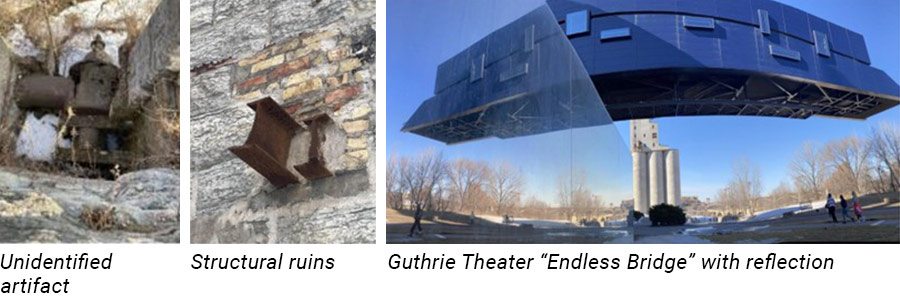

Examples of existing conditions which informed her design included steep drop-offs, embedded objects, objects seeming to float impossibly, and the presence of ruins and metal artifacts at varying degrees of decay scattered about an otherwise rocky and earthen site, as shown in the following images:

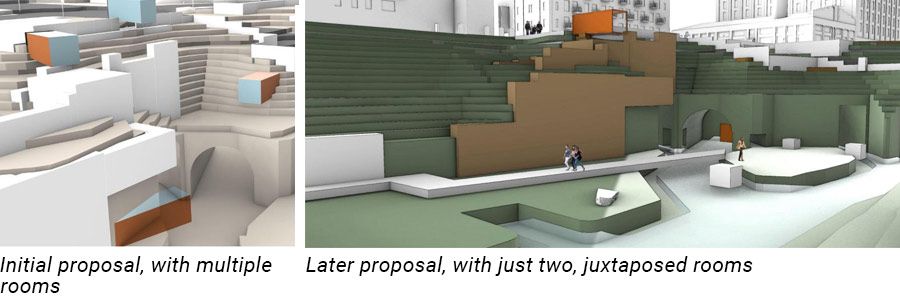

In response to these conditions, the student initially proposed a series of small rooms, positioned within the site to inhabit, view, and embody a range of existing conditions which evoked the sense of peril and thrill for her. By the end of her design process, she had distilled this series of rooms into just two, which exemplified and juxtaposed opposite ends of her topic’s experiential spectrum. Both rooms were clad in Corten (rusted) steel, reminiscent of the many rusted metal artifacts found on the site.

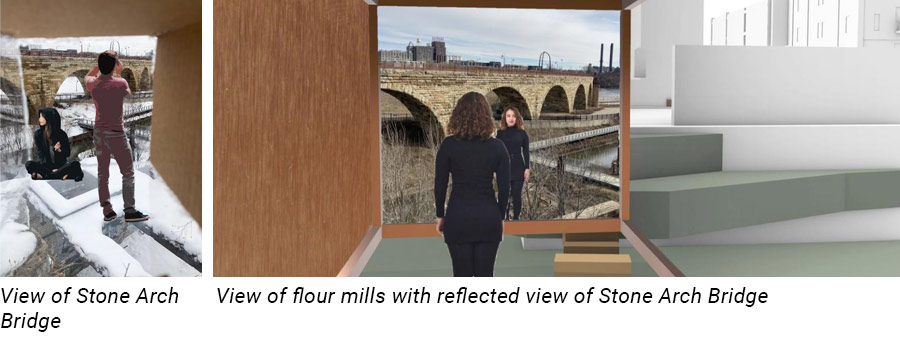

The first room of her final design proposal was located at the highest point of the site, set on top of an inset pedestal so it appeared to float above the ground plane. The gap between the ground plane and the structure gave the impression of a light-weight structure and deliberately required the visitor to step up and leave the ground plane to enter the room.

In addition, the room cantilevered precariously over the edge of an old retaining wall.

Apertures were positioned to frame views of the historic Stone Arch Bridge in one direction and historic flour mill building ruins served by that bridge in the other direction—at one location utilizing a mirror to place these two views side-by-side for the occupant.

This room was comprised of thin walls and given a wide and spacious entrance. It was designed with ample daylight and a tall ceiling allowing occupants to stand easily in the space. This room was outwardly focused on views at varying distances.

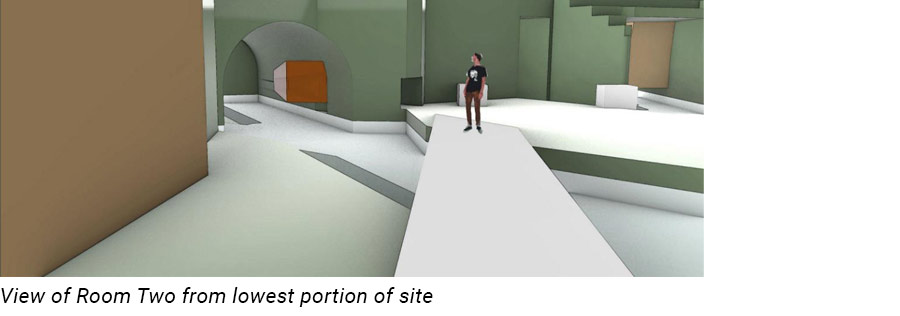

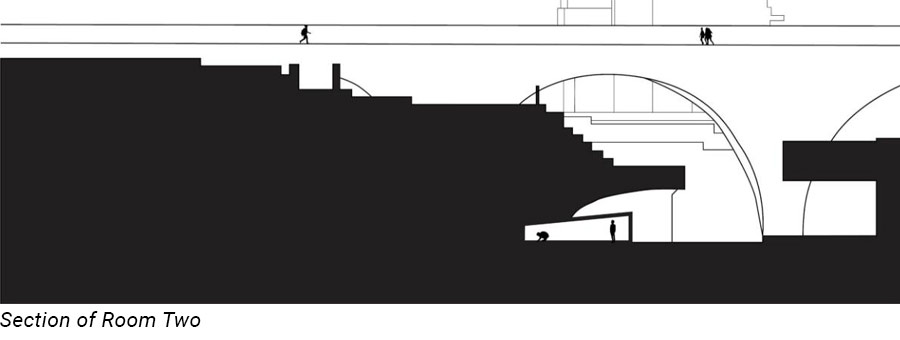

In contrast, the second room was located at a low point in the site, in the mouth of an abandoned raceway tunnel that had once served the flour mills. One corner of the room cantilevered visibly over the water outflow while the remainder was buried in the earth adjoining the tunnel.

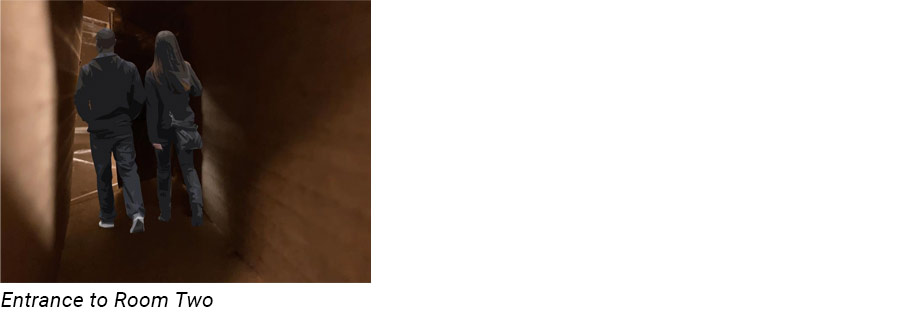

This second room was given a narrow and elongated entrance, giving the impression that the room had thick walls.

The room was kept relatively dark and designed with a low, sloped ceiling that required a visitor to crouch or crawl to occupy the farthest recesses of the room.

The room was inwardly focused, with occupants able to reach out and touch portions of the abandoned raceway structure.

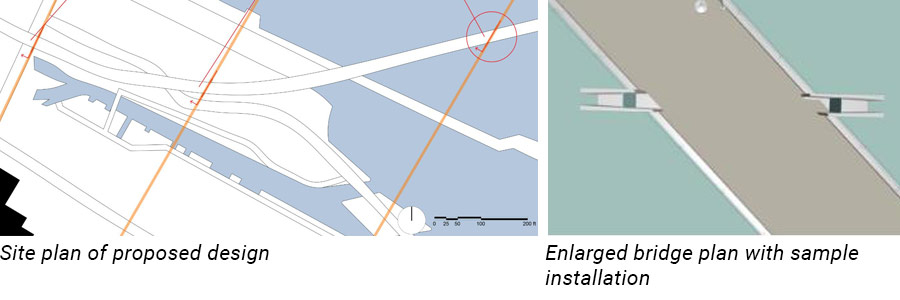

Student Iris Carroll, in the University of Minnesota BS Arch degree program, proposed a project entitled “Invisible Bridges” in 2021, in which she indicated: “The installation utilizes a series of curated views to reveal the ‘invisible bridges’ of the [existing] street grid on the site.”

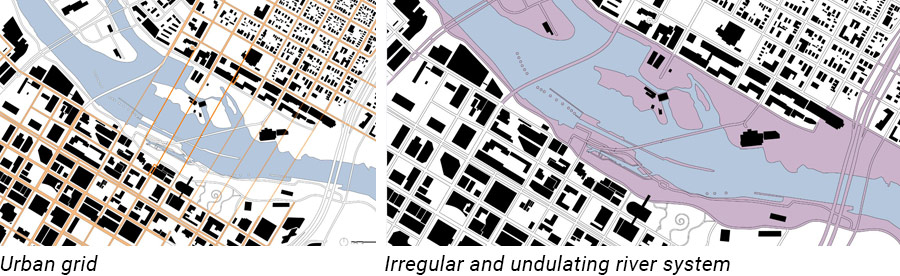

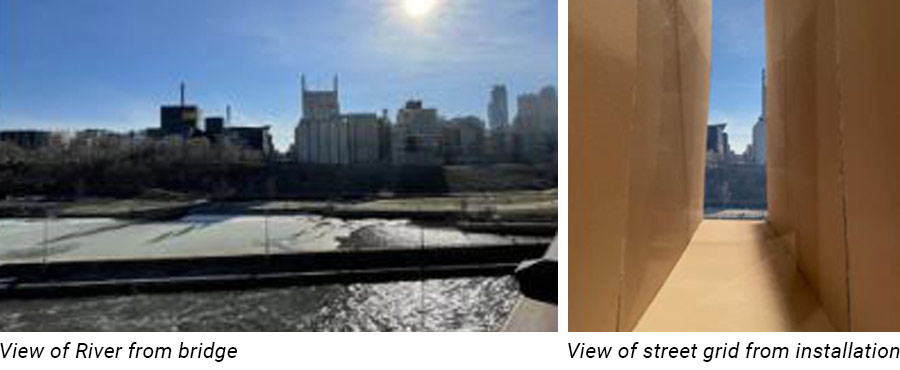

Her design was driven by the structured and enclosed quality of the urban street grid, which aligned across the Mississippi River at this location, juxtaposed against the irregular and expansive qualities of the river, including its various islands, embankments, and bridges, as delineated in the following images:

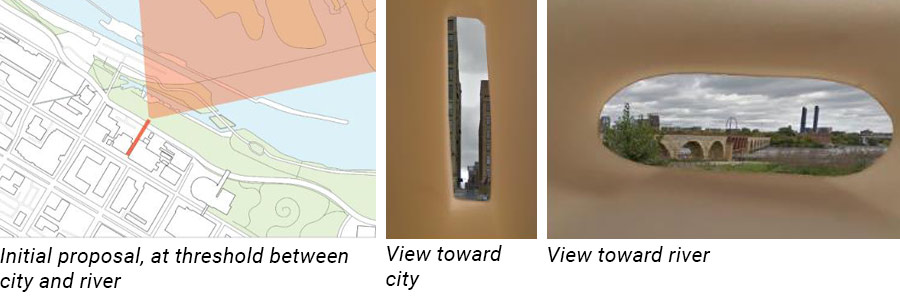

In response to these conditions, the student initially proposed highlighting a single transitional moment where the vertically structured, cavernous street grid gave way to the more horizontal, unbounded, and free-form qualities of the river valley.

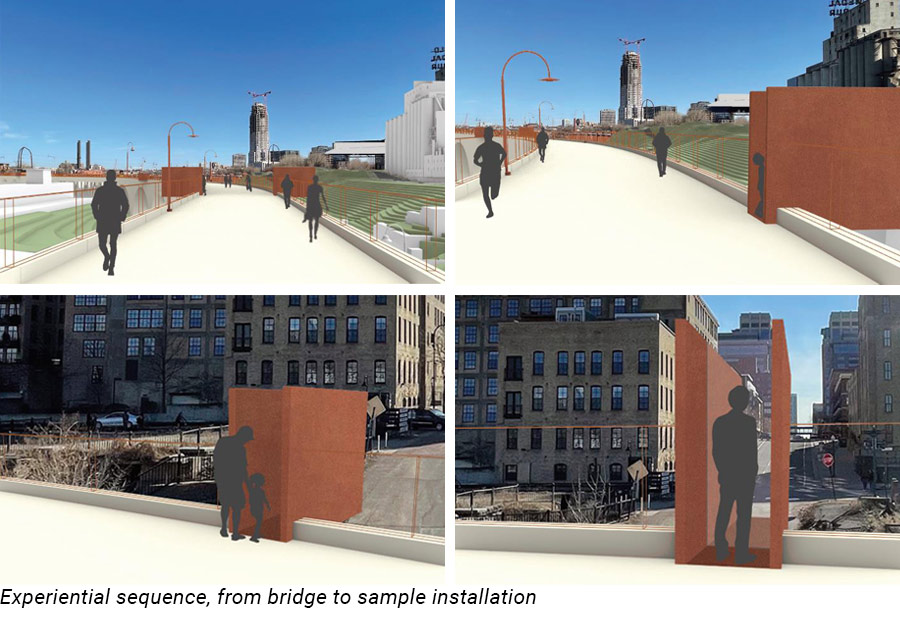

For her final design proposal, the student used the existing pedestrian Stone Arch Bridge as the foundation for a series of complementary installations.

The existing bridge served to convey the experience of the river valley through its undulating form and water-focused views. A series of viewing chambers aligned with the urban street grid were added at intervals along this bridge, orienting the viewer’s gaze back to city, giving form to and allowing occupants to experience the alignment of the streets across the banks of the river. A pedestrian walking along the bridge would experience wide open and horizontal views of the river and its banks, broken periodically by narrow, vertically framed views looking down the aligned city streets.

The juxtaposition of meandering bridge and flowing river set against gridded and well-defined streets served to heighten the experience of each; though the student had not designed the Stone Arch Bridge, the addition of the street-viewing portals drew the bridge actively into the design, highlighting its role as an expression of the river and river valley.

Conclusion

There are many possible interpretations of site-sourced architecture. As it is described in this article, site-sourced refers to form-making which engages the occupant in active and sensory ways to enhance their experience and understanding of certain pre-existing conditions. This site-sourced architecture is unextractable from the site since it relies on the site itself to provide the essential design ingredients. Site-sourced architecture as described in this article does not necessarily equate with sustainable architecture—it does not obligate sustainability as a stance. For example, an installation which enhances our awareness and appreciation of nature could or could not be constructed in a sustainable fashion. Similarly, an installation that heightens our awareness of a place need not expressly reflect that place. Even an installation in complete contrast to existing conditions can serve to enhance our nuanced awareness or understanding of existing conditions, through comparison.

An important part of the site-sourced design process involves introspection—the examination or observation of the designer’s own mental, sensory, and emotional processes to understand the mechanisms by which their personal experiences can be curated to similar effect for others. Imagine a lecture where a speaker has been presenting for some time at an unvarying volume and tempo, to the extent that the audience is losing focus. The audience is likely to snap to attention if the speaker abruptly changes their delivery, shouting excitedly. The experience may even prove memorable for them. If we understand the mechanism at work that piques the audience’s interest in this example – a noticeable break in pattern – we can then apply that knowledge to design. The designer is encouraged to explore an unfamiliar site in highly personal and sensory ways in the site-sourced design process. At the same time, it is also important for them to pay attention to the physical and cognitive processes engaged during their explorations, harnessing the mechanisms of perception to help to make the designer’s personal experiences transferrable to others.

Endnotes

1 David Heymann. “Site, Ascendant,” Places Journal, December 2010, 1. https://doi.org/10.22269/101213

2 David Heymann. “Site, Ascendant.” Places Journal, December 2010, 2. https://doi.org/10.22269/101213

3 Christophe Girot. “Four Trace Concepts in Landscape Architecture,” in Recovering Landscape: Essays in Contemporary Landscape Architecture, ed. James Corner (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1999), 60.

4 Christophe Girot. “Four Trace Concepts in Landscape Architecture,” in Recovering Landscape: Essays in Contemporary Landscape Architecture, ed. James Corner (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1999), 66.

5 Juhani Pallasmaa. The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses. Chichester: Wiley-Academy, 2005, 72.